“all nationalism essentially opposed to the traditional outlook” – Rene Guenon

“modernization without Westernization” – Alexander Dugin

“Eurasianism is a tradition of our political thought. It has deep roots in Russia and now takes on a completely new meaning, especially in light of the intensification of integration processes in the post-Soviet space” – Vladimir Putin

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine stands as a case which underscores the renewed escalation of power competition in Eurasia where states manoeuvre for influence, security, and greater power. Such an event provides the opportunity to use theoretical frameworks through which state behaviours and motivations can be interpreted. Theories such as realism and liberalism offer a materialistic lens focussing on military, economic and diplomatic strategy but which can fail to consider the holistic situation of international politics (Keohane 1984; Waltz 1979). Constructivism places emphasis on the influence of ideas, shared beliefs, cultural norms, and historical narratives in shaping the nature of statecraft security, foreign policy, and international relations between nation states (Wendt 1999).

It can be argued that the Russian-Ukraine conflict is deeply rooted in shared histories, perceived threats, nationalist fervour, and identity politics which can often be overlooked by conventional security theories (Hopf 1988; Barkin 2003). This article will cover the constructivist perspective as an alternative view to explore Russia’s motivations in its engagement with Ukraine and provides an analysis as to how NATO member Turkey can potentially negotiate to find a resolution. Stability may not come through military or economic sanctions but through shared beliefs and cultural narratives that may influence state actions and outcomes.

Russia’s conflict with Ukraine highlights its ambition to assert itself to be a leading power in Eurasia. Yet, it also represents Russia’s internal struggle of identity, culture, and prestige to preserve its power amidst the challenges of a globalised liberal world order, while facing external threats towards its own security (Wesson 1974; Mankoff 2012). Historically, the power dynamics in Eurasia follows a trajectory and cyclical pattern distinguished by empires and civilisations. State nations including Russia, Turkey, Iran, India, and China see themselves as civilisational states transcending the concept of modern nation states.

Culture, language, history, and religion are essential for soft power which bolsters their assertive great power status. This cultural and historical foundation legitimizes their power responses to any perceived threats that jeopardises their sovereignty and security. Homogeneous philosophy, sociology, idealism, and orientalism have influenced states actions and policies (Mankoff 2022). The constructivist view challenges the conventional view that international relations is solely about material power emphasizing instead the power of shared collective beliefs to drive transformative change.

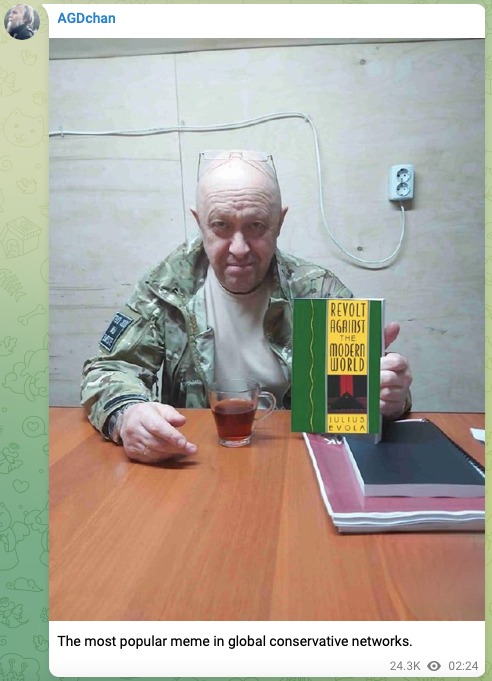

The doctrine of Russian Eurasianism (political theology) has reconstructed the identity and role of Russia to mobilise against Western coercion and influence within Eurasia. Eurasianism and Islam rose to prominence after the fall of the USSR which filled the ideological vacuum left after communism within the post-soviet space. Eurasianism became a framework and strategy for Russia to balance relations between Europe (the West) and Asia (the East) as well as for Russia to have its own independent political identity and sovereignty (Shlapentokh 2008; Palat 1993; Clowes 2011; Rangsimaporn 2006; Sériot 2014; Heinzig 1983). Simultaneously, Russia and Eurasianism found a common understanding and cause among disgruntled conservatives, traditionalists, populists, progressives, communists and nationalists against Western hegemonic liberal imperialism and colonialism (Diesen 2019; Gürcan 2013; Lyons 2014; Michael 2019; Upton 2018). Eurasianism represents the Russian idea (Byzantinism, Third Rome and Katechon) going back to the Slavophiles and the contentious philosophers Pyotr Chaadayev and Konstantin Leontiev which inspired the discourse on Russia’s standing within world history.

The innovative authors of Eurasianism such as Nikolai Trubetzkoy, Lev Gumilyov, Pyotr Savitsky, Konstantin Chkheidze, Lev Karsavin, Alexander Prokhanov, Gennady Zyuganov, Vladimir Zhirinovsky, Aleksandr Panarin, Mikhail Titarenko and Alexander Dugin (who is financially backed by the media mogul and oligarch Konstantin Malofeev) have all contributed to preserving Russia’s civilisational identity and culture (Russian World).

The Eurasianists view Russia as an imperial civilisational state incorporating the diversity of multiple ethnicities, cultures and religions within its own nationalist culture and hegemonic sovereignty. A Pan-Eurasian identity that transcends national civil boundaries through polycentrism. (Vinkovetsky 2000; Kipp 2002; Peunova 2008; Tchantouridze 2001; Shlapentokh 2017; Shlapentokh 2021; Savkin 1995; Fenghi 2020). Ukraine has come to the crossroads between Western European and Eastern Eurasian integration and great power competition of political economic initiatives, empire building and civilisational spaces.

Political economic initiatives (agendas) that are tied to cultural civilisational identities and values are colliding within Eurasia. Unable to find a common synthesis among different ideologies (liberalism (internationalism) ((democracy)) and conservatism (nationalism)((autocracy))) to ensure political economic cohesion and security. The EU-NATO alliance has encroached into Russia’s regional security (sphere of influence) threatening Russia’s territorial integrity (sovereignty) that’s linked to Russia’s national identity (Eurasian Orthodoxy). Both Russia and Europe are seeking security within Eastern Europe (Eurasian space) through their institutions (EU-NATO and EAEU-CSTO) that represents their cultural identities and values (Diesen 2021; Diesen & Keane 2017).

The hard power (military conflict) that has manifested within Ukraine among Russia and the West is the struggle to integrate Ukraine into either of their own political economic systems, culture and identity. Both Europe and Russia suffer from historical memories over their borders with each other embedding the assertive combative security policies against each other (Kassab 2018; Resende, Budrytė & Buhari-Gulmez 2018). Instead of the realists and liberals exacerbating the complexity between nation states either through power confrontations or diplomatic sanctions that only jeopardises stability. Constructivists can provide solutions through ideas and identity to create common understanding and compromise leading to material gains that ensures security.

NATO member Turkey has risen as a mediator between Russia and Ukraine during the conflict where strategic manoeuvring and diplomatic efforts can create negotiations for peace and security. Russia is economically reliant on Turkey for trade and investment which has shaped their relations to be noncombative. Turkey’s strategic geography places the EU-NATO alliance advantageously against Russia’s influence within Eurasia particularly the Balkans (mediator between Kosovo and Serbia) and the Caucuses (normalising relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan). Turkey’s ascension into the EU would accelerate other nations memberships into the EU-NATO alliance greatly diminishing Russia’s influence and strategic strategy. Turkey as a great power and civilisational state has lucrative influence within Eurasia through the Islamic civilisation (Pan-Islam) and the past Ottoman Empire (Pan-Turkism) that puts Russia at odds with its own geographical reality and identity. Turkey can give aspirations for special autonomy rights even independence towards Muslim regions of Russia who have been marginalised. (Şahin 2022; Torbakov 2017; Shlapentokh 2007; Ercan 2017). Securitising the adoption of Western ideals and values (religious freedoms, freedom of speech and democracy) through Islamic solidarity (Arvanitopoulos & Akyol 2009). The failure of the West to integrate Russia into Europe after the collapse of the USSR provides Turkey the opportunity to integrate Europe and Russia through Turkish Eurasianism.

Eurasian economic integration and development has become an alternative to Western liberal globalization. Eurasia has become a centre for global economic growth and development incentivizing policy reform, economic cooperation and good governance among Western and Eastern institutions and organisations (IMF, IBRD, EIB, WTO, OECD, BSEC, BRICS, SCO, EAEU, D-8, ECO and AIIB) (Lane & Samokhvalov 2014; Anagnostou & Panteladis 2015; Khondker 2020; Lukin 2020; Eldem 2022). The Islamic world can connect Europe and Asia along the middle corridor of Eurasia (Silk Road) to sustain global economic development securitizing energy.

Turkey as a leader of the Islamic world can integrate Europe with Central Asia through cultural historical ties to these regions (Organization of Turkic States (Pan-Turkism)). Security and stability will only prevail within Eurasia if there is cohesion between nation states within their respected regions. Chkheidze outlined the prerequisites for state cohesion with multiple ethnic religious cultures within the territories of Russia (influenced on culture by Trubetzkoy & Karsavin). Geopolitical unity (territorial integrity), ethnic unity (common ancestry) and cultural historical unity (common community and identity) (Шнирельман 2001). Where Russian Eurasianism has stumbled with Ukraine (Druzhinin 2016), Turkish Eurasianism can succeed in creating a common Eurasian community and identity bridging the divide between Russia and the West.

Prominent figures in Turkey have illustrated the practical aspects of Eurasianism and Eurasianization within their own schools of political thought (Neo-Ottomanism, Pan-Turkism and Kemalism). Such as Attila Ilhan, Turgut Ozal, Bulent Ecevit, Huseyin Kami Turk, Ahmet Davutoglu, Ramazan Ozey, Ozcan Yeniceri, Okan Ancak, Mehment Perincek and Dogu Perincek. Some view using Eurasianism solely for Turkey’s benefit expanding its influence as a regional power which will collide with many nations including Russia and Iran. Others particularly Perincek (influenced by Dugin) view Eurasianism as a means to create unity between Russia and Turkey forming a coalition against Western powers (Torosyan 2023; Torbakov 2017; Tuysuzoglu 2014; Shlapentokh 2016; Akturk 2004; Erşen 2022; Akçalı & Perinçek 2009; Erşen 2013). However, the clear problem with these scenarios is not just power competition, identity, history or culture but a split within religion.

The controversial Islamic philosopher Geydar Dzhemal explained that Russia’s historical cyclical trajectory (Russian Empire, Soviet Union & Modern Russia) has always been with Western Christian civilisation behaving as a brutal imperial colonialist against the Islamic world. To win favour within political, financial and security circles in the West to ensure its own great power prestige and national security (Shlapentokh 2008; Sibgatullina & Kemper 2017; Koçak 2017). Dzhemal viewed Turkey as a catalyst for global jihadism. The West supporting Turkish Eurasianism would provide a foundation for common identity forming common interest among nation states seeking security.

Social constructivism demonstrates the importance of shared ideas, values, history, culture and religion in forming a common identity in creating common interests among nation states seeking security. The West supporting Turkish Eurasianism would be an innovative approach to negotiating and resolving the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. Diplomatic hedging (security insurance seeking) is an opportunity for mutual compromise, cooperation and benefit for shared regional integration and governance. Representing a robust Eurasian community and identity that maintains security and peace within Eurasia (Dugin 2022).

More articles on Russian Eurasianism:

The Revenge of the Eurasianists: https://www.transformingthenation.com.au/the-revenge-of-the-eurasianists/

The Resurrection of Russian Eurasianism: https://www.transformingthenation.com.au/the-resurrection-of-russian-eurasianism/

Alexander Dugin: The Eurasian Occultist: https://www.dailyscanner.com/alexander-dugin-the-eurasian-occultist/

References:

Akçalı, E., & Perinçek, M. (2009). Kemalist Eurasianism: An emerging Geopolitical Discourse in Turkey. Geopolitics, 14(3), 550–569. Routledge Taylor & Francis.

Arvanitopoulos, C. & Akyol, M. (2009). Turkey’s accession to the European Union. What Makes Turkish Islam Unique? Pg 183-193. The Constantinos Karamanlis Institute for Democracy series on European and international affairs. Springer Berlin.

Akturk, S. (2004). Counter-Hegemonic Visions and Reconciliation through The Past: The Case of Turkish Eurasianism. Ab Imperio, 2004(4), 207–238. Project Muse.

Anagnostou, A., & Panteladis, I. (2015). Eurasian orientation and global trade integration: the case of Turkey. Eurasian Economic Review, 6(2), 275–287. Eurasia Business and Economics Society.

Barkin, J. S. (2003). Realist constructivism. International Studies Review, 5(3), 325–342. pp. 332-337. Wiley. JSTOR.

Clowes, E.W. (2011) Russia on the edge: Imagined Geographies and post-Soviet identity. Chapter 2 Postmodernist Empire Meets Holy Rus’: How Aleksandr Dugin Tried to Change the Eurasian Periphery into the Sacred Center of the World. Pg 43-67. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Diesen, G. (2021). Europe as the western peninsula of Greater Eurasia. Journal of Eurasian Studies, 12(1), 19–27. Hanyang University.

Diesen, G. (2019). Russia as an international conservative power: the rise of the right-wing populists and their affinity towards Russia. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 28(2), 182–196. Routledge Taylor & Francis.

Diesen, G., & Keane, C. (2017). The two-tiered division of Ukraine: historical narratives in nation-building and region-building. Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, 19(3), 313–329. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Druzhinin, A. G. (2016). Russia in Modern Eurasia: The vision of a Russian geographer. Quaestiones Geographicae, 35(4), 71–79. Russian Humanitarian Science Foundation.

Dugin, A. G. (2022). Eurasianism as a Non-Western Episteme for Russian Humanities: Interview with Alexander G. Dugin, (Dr. of Science, Political Sciences, Social Sciences), Professor, Leader of the International Eurasian Movement. Interviewed by M.A. Barannik. Вестник Российского Университета Дружбы Народов, 22(1), 142–152.

Eldem, T. (2022). Russia’s War on Ukraine and the Rise of the Middle Corridor as a Third Vector of Eurasian Connectivity: Connecting Europe and Asia via Central Asia, the Caucasus and Turkey. German Institute for International and Security Affairs. Centre for Applied Turkey Studies.

Erşen, E. (2022). Turkey and the Eurasian Integration: ideology or pragmatism? Вестник Российского Университета Дружбы Народов, 22(1), 111–125.

Ercan, P. G. (2017). Turkish Foreign Policy: International Relations, Legality and Global Reach. Pehlivantürk, B. Chapter 13: East Asia in Turkish Foreign policy: Turkey as a ‘Global Power’? In Springer eBooks (pg 259–278). Palgrave Macmillan.

Erşen, E. (2013). The evolution of ‘Eurasia’ as a geopolitical concept in Post–Cold War Turkey. Geopolitics, 18(1), 24–44. Routledge Taylor & Francis.

Fenghi, F. (2020). It will be fun and terrifying: Nationalism and Protest in Post-Soviet Russia. Chapter 4: Aleksandr Dugin’s Conservative Postmodernism, pp. 129-158. The University of Wisconsin Press.

Gürcan, E. C. (2013). NATO’s “Globalized” Atlanticism and the Eurasian Alternative. Socialism and Democracy, 27(2), 154–167. Routledge Taylor & Francis.

Heinzig, D. (1983). Russia and the Soviet Union in Asia: Aspects of Colonialism and Expansionism. Contemporary Southeast Asia, Vol 4, No 4. pp. 417-450. ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. JSTOR.

Hopf, T. (1998). The promise of constructivism in international Relations theory. International Security, 23(1), 171–200. pp. 180-181. The MIT Press. JSTOR.

Kassab, H. S. (2018). Grand strategies of weak states and great powers. Chapter 6: Neoempires Under Construction: The European Union and Eurasian Union. pp. 141-160. Palgrave Macmillan.

Keohane, R.O. (1984). After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Khondker, H. H. (2020). Eurasian globalization: past and present. Globalizations, 18(5), 707–719. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Kipp, J. W. (2002). Aleksandr Dugin and the ideology of national revival: Geopolitics, Eurasianism and the conservative revolution. European Security. 11:3. 91-125. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Koçak, M. (2017). The roots of security narratives on Islam in Russia: Tatar yoke, official religious institutions, and the Western influence. Insight Turkey, 19(4), 137–154.

Kipp, J. W. (2002). Aleksandr Dugin and the ideology of national revival: Geopolitics, Eurasianism and the conservative revolution. European Security. 11:3. 91-125. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Lane, D., & Samokhvalov, V. (2014). The Eurasian Project and Europe: Regional Discontinuities and Geopolitics. Palgrave Macmillan.

Lukin, A. (2020). The “Roads” and “Belts” of Eurasia. Palgrave Macmillan.

Lyons, M (2014). Exchange on Eurasianism. Socialism and Democracy, 28(1), 165–168. Routledge Taylor & Francis.

Mankoff, J. (2022). Empires of Eurasia: How Imperial Legacies Shape International Security. Yale University Press.

Mankoff, J. (2012). Russian Foreign Policy: The Return of Great Power Politics. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Michael, G. (2019). Useful Idiots or Fellow Travelers? The Relationship between the American Far Right and Russia. Terrorism and Political Violence, 31(1), 64–83. Routledge Taylor & Francis.

Palat, K. M. (1993). Eurasianism as an Ideology for Russia’s Future. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol 28, No 51. Pg 2799-2809. JSTOR.

Peunova, M. (2008). An Eastern Incarnation of the European New Right: Aleksandr Panarin and New Eurasianist Discourse in Contemporary Russia. Journal of Contemporary European Studies. 16:3. 407-419. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Rangsimaporn, P. (2006). Interpretations of Eurasianism: Justifying Russia’s role in East Asia. Europe-Asia Studies, 58(3), 371–389. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Resende, E., Budrytė, D., & Buhari-Gulmez, D. (2018). Crisis and change in Post-Cold War global politics: Ukraine in a Comparative Perspective. Chapter 10. The Self-Other Space and Spinning the Net of Ontological Insecurities in Ukraine and Beyond: Reconstructions of Boundaries in the EU Eastern Partnership Countries Vis-a-Vis the EU and Russia. Pg 225-254. Springer.

Savkin, I (1995) “If Russia Is to Be Saved, It Will Only Be Through Eurasianism”, Russian Studies in Philosophy, 34:3, 62-76. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Şahin, D. (2022). Turkey’s foreign policy in Post‐Soviet Eurasia. Middle East Policy, 29(2), 67–84. Cyprus Policy Center, Eastern Mediterranean University.

Sériot, P. (2014). Structure and the whole: East, west and non-darwinian biology in the origins of structural linguistics. Chapter 2 The Eurasianist Movement. Pg 24-60. De Gruyter, Inc.

Shlapentokh, D (2021). Ideological Seduction and Intellectuals in Putin’s Russia. Palgrave Macmillan. Springer

Shlapentokh, D (2017). Alexander Dugin’s views of Russian history: collapse and revival, Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe, 25:3, 331-343. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group

Shlapentokh, D (2016). The Ideological Framework of Early Post-Soviet Russia’s Relationship with Turkey: The Case of Alexander Dugin’s Eurasianism. Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, Vol 18. Pg 263-281. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Shlapentokh, D. (2008). Islam and Orthodox Russia: From Eurasianism to Islamism. Communist and Post-communist Studies, 27-46. Pg 34-45. University of California Press

Shlapentokh, D. (2007). Russia between East and West: Scholarly Debates on Eurasianism. Wiederkehr, S (translated by Keller, B & Simer, E). Chapter 2 Eurasinaism as a Reaction to Pan-Turkism. Brill

Shlapentokh, D (Various Years). [Multiple Works]. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group/University of California Press/Palgrave Macmillan.

Sibgatullina, G., & Kemper, M. (2017). Between Salafism and Eurasianism. Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations, 28(2), 219–236. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Tchantouridze, L. (2001). Eurasianism: In Search of Russia’s Political Identity: A Review Essay. No. 16, Pg 69-80. Institute of International Relations. JSTOR.

Torosyan, V. (2023). Multi-faceted Eurasianism: a comparison in practice. Review of Economic and Political Science.

Torbakov, I. (2017). Neo-Ottomanism versus Neo-Eurasianism? Nationalism and Symbolic Geography in Postimperial Turkey and Russia. Mediterranean Quarterly, 28(2), 125–145. Duke University Press.

Tuysuzoglu, G (2014). Strategic Depth: ANeo-Ottomanist Interpretation of Turkish Eurasianism. Mediterranean Quarterly 25:2. Mediterranean Affairs.

Upton, C. (2018) Dugin against Dugin: A Traditionalist critique of the fourth political theory. Reviviscimus.

Vinkovetsky, I. (2000). Classical Eurasianism and Its Legacy. Canadian American Slavic Studies. 34. No 2. 125–39. Brill.

Waltz, K.N. (1979) Theory of International Politics. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.

Wesson, R. G. (1974). The Russian Dilemma: A Political and Geopolitical View. Rutgers University Press.

Wendt, A. (1999). Social Theory of International Politics. Cambridge University Press.

Шнирельман, В. А. (2001). The Fate of Empires and Eurasian Federalism. Inner Asia, 3(2), 153–173. Pg 156. Brill.Top of Form

Гейдар Джемаль: «С Эрдоганом Турция займет антироссийскую позицию и будет наращивать поддержку крымских татар» | КОНТРУДАР || Гейдар Джемаль. http://www.kontrudar.com/vistupleniya/geydar-dzhemal-s-erdoganom-turciya-zaymet-antirossiyskuyu-poziciyu-i-budet-narashchivat

Гейдар Джемаль. (2015, December 3). Discourse between Yaqub Zaki and Geydar Dzhemal. Political islam, neo-ottoman project, Russia, China [Video]. YouTube.